I was running my AI-powered release risk agent against a set of Eval test cases when something interesting happened. The system threw an error — and it was exactly the right thing to do.

[error] assessment_failed

error="Risk score is 0.95 (> 0.7) but decision is GO.

High-risk releases should be NO_GO."

Let me explain what happened, why it matters, and what it taught me about building reliable systems on top of LLMs.

The Setup

I’m building a release risk assessment agent — an AI system that reviews pull requests and decides whether they’re safe to deploy. It looks at file changes, CI results, commit messages, and other metadata, then returns a structured assessment: a risk score, risk level, and a GO/NO_GO decision.

The architecture has three layers:

- LLM Layer — GPT-4 analyzes the release data and returns a risk assessment

- Policy Engine — Deterministic rules that can override or adjust the LLM’s output (e.g., “any CI failure is an automatic NO_GO”)

- Validation Layer — Pydantic models that enforce consistency constraints on the final output

What Went Wrong (And Right)

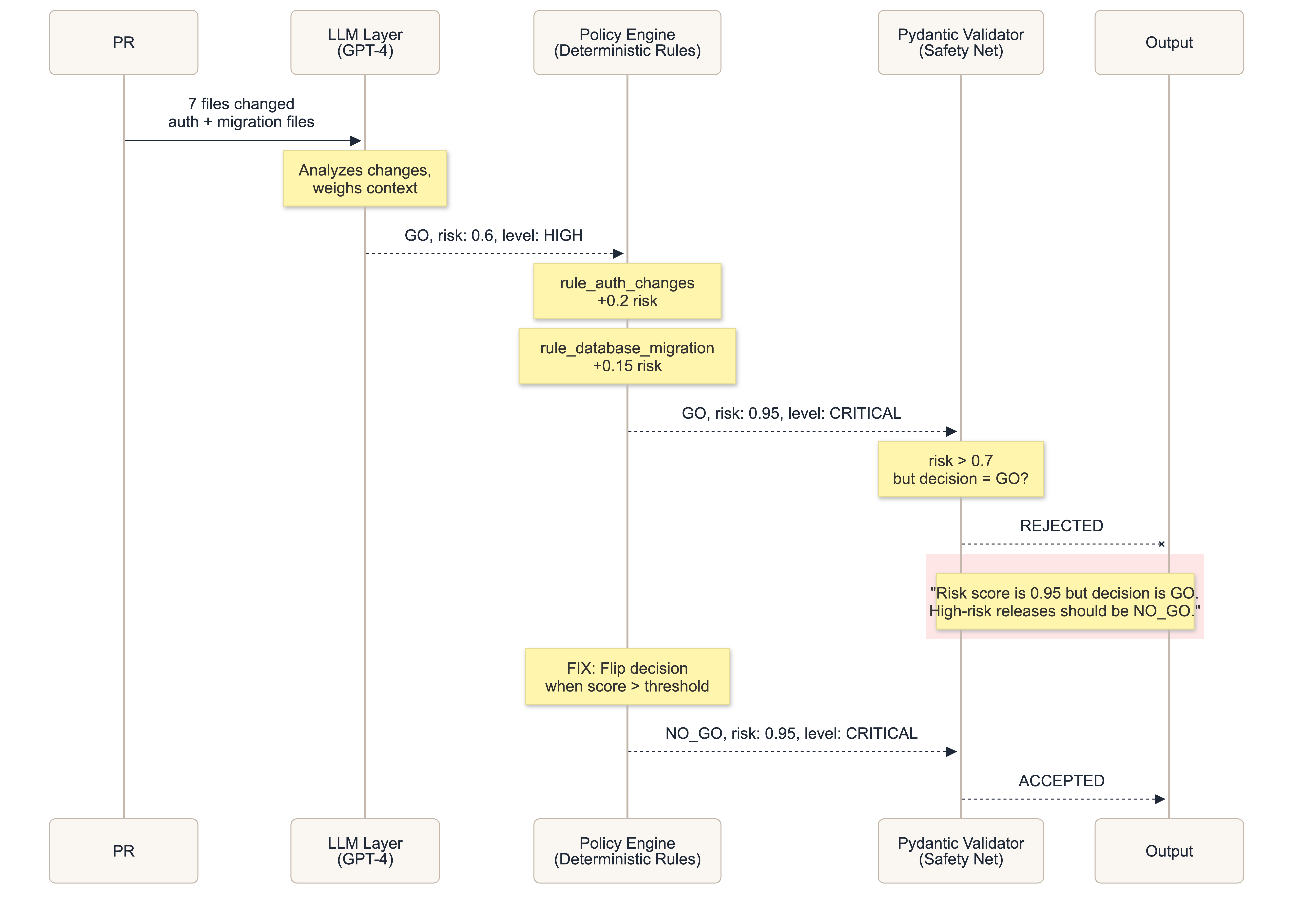

Here’s the sequence of events for PR #104, which contained changes to authentication files:

Step 1: The LLM returned a reasonable assessment.

The model looked at the PR and said: GO, risk score 0.6, risk level HIGH. It recognized the auth changes were significant but felt the release was still safe enough to proceed. A judgment call. Not unreasonable.

Step 2: The policy engine intervened.

The deterministic policy rules kicked in. The rule_auth_changes policy detected modifications to authentication files and bumped the risk score by +0.2. The rule_database_migration policy added another +0.15. The final risk score landed at 0.95 — firmly in critical territory.

But here’s the problem: the policy engine adjusted the score without flipping the decision. The LLM’s original GO decision was still attached to what was now a 0.95 risk score.

Step 3: Pydantic caught the inconsistency.

The output model has a validator that enforces a simple invariant: if the risk score exceeds 0.7, the decision must be NO_GO. A score of 0.95 with a GO decision is contradictory. The validator rejected the output and raised an error.

The system refused to return a dangerous answer.

Why This Is a Feature, Not a Bug

My first instinct was to “fix” this by making the policy engine smarter. And yes, that’s the right engineering fix (we’ll get to that). But step back and appreciate what happened:

Three independent safety layers, each with a different perspective, worked together.

- The LLM used judgment. It weighed the changes and made a call.

- The policy engine used rules. It applied deterministic, non-negotiable adjustments based on file patterns.

- The validation layer used constraints. It enforced logical consistency on the final output.

No single layer was wrong in isolation. The LLM’s original assessment was defensible. The policy engine’s risk adjustments were correct. The problem only emerged when their outputs were combined — and the validation layer was the one that caught it.

This is defense in depth applied to AI systems.

The Broader Lesson: Don’t Trust Any Single Layer

When building applications on top of LLMs, it’s tempting to think of the model as the brain and everything else as plumbing. But LLMs are probabilistic. They can be confidently wrong. They can be manipulated. They can hallucinate.

Here’s what a layered approach gives you:

Layer 1: The LLM (Flexible, But Unreliable)

The model provides nuanced analysis that no set of rules could replicate. It understands that a database migration in a payment system is riskier than one in a logging module. But it might also decide a PR titled “minor fix” is safe even when the files include DROP TABLE users.

Strength: Nuance and reasoning. Weakness: Inconsistency and overconfidence.

Layer 2: Deterministic Rules (Rigid, But Reliable)

Policy rules don’t care about context. If CI fails, the answer is NO_GO. If auth files change, the risk goes up. No exceptions, no reasoning, no judgment.

Strength: Predictability and auditability. Weakness: No nuance. Can’t handle novel situations.

Layer 3: Schema Validation (The Last Line of Defense)

Pydantic validators enforce structural invariants. They can’t tell you what the right answer is, but they can tell you when an answer is self-contradictory. A 95% risk score with a GO decision isn’t just wrong — it’s incoherent.

Strength: Catches logical impossibilities. Weakness: Only catches constraint violations, not bad judgments.

The Fix

The engineering fix is straightforward. After the policy engine finishes adjusting scores, check whether the final score exceeds the threshold and flip the decision accordingly:

# After all policy rules have been applied

if output.risk_score > threshold:

output.decision = Decision.NO_GO

But notice: even after this fix, the Pydantic validator should stay. It’s a safety net. The best safety nets are the ones that never trigger — but you don’t remove the net just because the trapeze artist hasn’t fallen yet.

Takeaways for Anyone Building on LLMs

- Never rely on the LLM alone for safety-critical decisions. Add deterministic rules that can override the model. An LLM can be prompt-injected into saying a dangerous release is safe. A policy rule checking CI results cannot.

- Validate the final output, not just the model’s output. Your post-processing pipeline (policy rules, transformations, enrichment) can introduce inconsistencies that weren’t in the original model response.

- Make your constraints explicit. The Pydantic validator that caught this issue is a one-line check:

if risk_score > 0.7 and decision == GO: raise error. Write down the invariants your system should never violate, then enforce them in code. - Log everything. The structured logging in the agent made this issue immediately visible. I could see the assessment start, the LLM’s response, the policy adjustments, and the exact validation failure — all in one trace. Without this, the error would have been a mystery.

- Treat errors as signal, not noise. This validation error wasn’t a bug to squash. It was the system telling me about an architectural gap between two layers. Every error your safety net catches is a lesson about where your system’s assumptions break down.

Final Thought

The goal isn’t to build an AI system that never makes mistakes. The goal is to build one where mistakes are caught before they reach the user. Three imperfect layers, each watching the others, are more reliable than one “perfect” layer.

My release agent threw an error. And that was the best thing it could have done.